The Visual History of the

Smilin' Buddha Cabaret

The

title of this project is “The Visual History of the Smilin'

Buddha Cabaret.” This

does not mean that I intend to simply tell the story of the Smilin'

Buddha through photos and video, but that I want to understand the

way its story has been, and is being, told through photography and

film. While I want to keep the Smilin' Buddha as the focus of this

visual history (or history of visuals), it will, at times,

be

necessary to discuss the

larger history of the Downtown Eastside (DTES)

and the City of Vancouver to add to the “thick description” of

the Smilin' Buddha story. The

images that represent the memory of the early-Smilin' Buddha should

not

be considered accurate

representations of the way people

saw or thought of the club at the time. While these images provide a

different perspective of the past, their importance has largely only

been recognized within the last decade as shows at the Vancouver Art

Gallery (VAG) and Museum of Vancouver (MOV) have highlighted under

appreciated aspects of Vancouver's history through

exhibitions on its neon

heritage and the street

photography of Fred Herzog. These

neon signs and photographs are, like the Smilin' Buddha, part of

Vancouver's cultural history, but

they are also part of an effort to redefine the club, the DTES neighbourhood, and the larger city. In this way, the

significance of the visual history of the Smilin' Buddha is not in

how the images represent the past, but how they are used in the

present.

It

is not clear when or why

the Smilin' Buddha Cabaret closed for good. Several

sources suggest it closed in

1987, others

place this date as late as

1993 when a fire gutted the club,

1

but it hardly seems to matter. As far as I can tell, there was no

eulogy for the end of the Smilin'

Buddha. By

the late-1980s the Vancouver punk scene was either dead or had moved

on from the club at 109 East Hastings Street and

it doesn't appear that anyone else came to fill their place.

When the

Smilin' Buddha reappeared in a 1993 Vancouver Sun article, it

was to announce

that the large neon sign (seen at the top of this page) could

be purchased for $3000 from

a neon company in Burnaby.2

That the band 54-40 purchased

the sign, named their 1994 album after the club, and used the sign as

a backdrop on tour is an important, if well-told, part of the Smilin' Buddha story.

But perhaps more importantly

for the legacy of the club, the band donated the sign to the MOV in the mid-2000s where it is now on permanent display in

the You Say You Want a Revolution

gallery.

Fred Herzog

|

| Fred Herzog "Hastings at Columbia 2" 1958 |

|

| Fred Herzog "Hastings at Columbia" 1958 |

The

MOV says that the Smilin'

Buddha “was at the centre

of Vancouver's changing entertainment scene for decades [and] in the

1950s . . . was

a symbol of Vancouver's post-war prosperity and bustle as captured in

the photographic work of Fred Herzog,” most likely referring to two

photos taken in 1958, both titled “Hastings at Columbia.” While

the “bustle” in these photographs is evident,

it is questionable what exactly the Smilin' Buddha represented at

this time, or how this bustle

in the photo

relates to the

Smilin' Buddha beyond its proximity within Herzog's frame.

Since these photos are taken

in the late-afternoon on a

Sunday (judging from the shadows and the newspaper in the second

photo), this

would mean that it was hours before the Smilin' Buddha's nightly

entertainment would begin. Like most of the East End clubs, the

Smilin' Buddha was still a bottle club at this time--an

unlicensed cabaret that

attracted patrons with

entertainment and sold food, ice

and drink mixes while the

patrons brought in their own booze that they kept hidden

away in case of raids by police or liquor squad detectives.3 Without entertainment, beer,

or liquor sales (unless sold illegally)

it is unlikely that the club would be open at

the time of Herzog's photo.

|

| Fred Herzog "Hub and Lux" 1958 |

The

MOV's sentence should probably read, “the Smilin' Buddha has

become a symbol of Vancouver's

post-war prosperity” since

this signification appears

to be the result

of the preservation, stories,

and myths

that have sustained and amplified the memory and

legend of the Smilin' Buddha,

rather than

with any idea actually

expressed in the 1950s. Next to the MOV's

own photos of the

Smilin' Buddha's

neon sign, Fred Herzog's

photos have probably become the most frequently

reproduced images of the

club.

Herzog must have been

attracted to the sign, since it features so prominently

in both “Hastings at Columbia” photos, yet it is questionable

whether it held the same iconic status for him as it appears to hold

for many people today. Both “Hub and Lux” also

taken in

1958, just one block west of

the Smilin' Buddha, and “Arthur Murray” taken in

1960 from the corner of

Hastings and Cambie, show scenes more closely focused on the neon

signs of Vancouver, taken at night when their effect is more fully

realized. Add to these some of Herzog's many photos of the Granville

strip, and the image of the Smilin' Buddha place as “the centre of

Vancouver's changing entertainment scene,” becomes questionable

unless the emphasis is placed

on the changes

in entertainment at the club.

|

| Fred Herzog "Arthur Murray" 1960 |

As much as Fred Herzog's photos have come to represent 1950s and 60s Vancouver today, it is important to recognize that his work did not receive widespread recognition at the time. It was not until 2007 that his first book of photographs was published and he received a career retrospective at the VAG. Part of what makes Herzog's photos distinctive today is the same thing that kept his work from being considered “serious” art and more widely reproduced at the time he was taking them: his use of colour. Not only was colour film harder and more expensive to print, it was also considered kitschy, vulgar, and both “distorting” and “too damn real for its own good.”4 On one hand, Claudia Gochman explains that because the medium of photography was thought of “as a window to the world, possess[ing] an intrinsically documentary value, [it] had a duty to maintain a sense of seriousness” that, for whatever reason, colour could not maintain.5 On the other hand, New York Times photography critic, A.D. Coleman, cited in Grant Arnold's introduction to Herzog's Vancouver Photographs, wrote that “the abstraction inherent in black-and-white photography . . . makes possible layers of meaning which are beyond the reach of color photography."6

|

| Fred Herzog "Arcade" 1968 Taken from the Northwest corner of Main & Hastings. |

The debate about the value and use of colour in photography from the 1950s-70s has shifted to debates about the value and use of street photography today. In Unfinished Business: Vancouver Street Photographs 1955 to 1985, Bill Jeffries writes “street photographs are powerful social documents dense with information, almost always open to conflicting interpretations, and conflicting attributions of 'quality.'”7 That Herzog's photos are so frequently used to represent Vancouver's past suggests their aesthetic value, but it doesn't consider what his artistic vision was. Helga Pakasaar, for instance, writes that Herzog's photos “are vulnerable to a nostalgic reading, yet [he] avoids any glorification of the past or desire for historical continuity;”8 Stephen Osborne, similarly, writes that “appearances in the city beckon to the camera in the present tense, and the camera responds. Hence there is no posterity presumed in these photographs, no rhetoric of preservation or glorification.”9 Yet, Herzog says, “I pictured myself having to show what the city looked like to people maybe 50 or a hundred years from now.”10

In interviews, Fred Herzog describes his style as “photo-realism:” a photographic equivalent to writers like Dos Passos and Flaubert. Grant Arnold describes this style as a “realism that value[s] detail and objective description over explicit authorial commentary.”11 In his own words, Herzog says “the photo-realist hopes to discover unseen treasures, picturesque disorder, over-the-top nasty disorder, naive art by housewives and gardeners, decay of all descriptions and the multicoloured results of misdemeanour, if not crime.”12 In this way, Herzog's descriptions of his own work appear to support contesting interpretations and uses of his photographs today. His photos are intended to be both realistic documents of a time and place showing “city vitality,” and an attempt to capture the “picturesque disorder” of these places.13

The question is, do these ideas of vitality and disorder contradict each other? This is an important question given the way popular narratives describe the DTES as a once vital part of the city that has decayed into a spectacle of homelessness and drug addiction. Michael Turner interprets Herzog's second “Hastings at Columbia” photo to represent Hastings Street's transition from city centre to “war zone,” noting that “the shadow over the Columbia street sign is telling, though nothing compared to those better-dressed long coats retreating from Herzog's camera.”14 While Herzog's other “Hastings at Columbia” photo doesn't lend itself to this anachronistic interpretation, the MOV similarly reads history backwards into these photos by suggesting that they show the Smilin' Buddha as a symbol of Vancouver's post-war prosperity. For Herzog, vitality doesn't seem to be linked to economics, but it is not clear if his photos, like “Howe and Nelson,” taken in 1960, show a “romanticism for an earlier Vancouver . . . scrubbed raw by 'wear, decay, and abandonment,'” as Michael Turner suggests,15 or whether he trying to offer a more substantive critique of modernism. Whatever the case, Herzog appears to lament the loss of “old” Vancouver to the encroaching modernism of Vancouver architecture exemplified by the civic planning initiative that led to the production of the 1964 short documentary To Build A Better City.

| ||||

| Fred Herzog "Man With a Bandage" 1968. |

|

| Fred Herzog "Howe and Nelson" 1960 |

Bev Davies

|

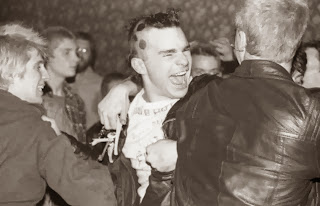

| Bev Davies - Black Flag at the Smilin' Buddha |

|

| Bev Davies - Smilin' Buddha Cabaret |

|

| Bev Davies - Smilin' Buddha crowd |

After the Smilin' Buddha

|

| Steve Addison - Hastings at Columbia 2012 |

| |

| The Smiling Sports Cafe - Still from Heroines |

1. Keith McKellar, Neon Eulogy:Vancouver Cafe and Street (Vancouver: Ekstasis Editions, 2001), 27.↩

2. John Mackie, "Hey Buddha, Got a Spare $3000," The Vancouver Sun, (10 June 1993): C2.↩

3. Becki L. Ross, Burlesque West: Showgirls, Sex, and Sin in Postwar Vancouver (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2009), 50-72.↩

4. Claudia Gochman, "Fred Herzog: In Colour," in Fred Herzog: Photographs(/i> (Vancouver: Douglas & McIntyre, 2011), 2; Grant Arnold, "Fred Herzog's Vancouver Photographs," in Fred Herzog: Vancouver Photographs (Vancouver: Douglas & McIntyre, 2007), 5. ↩

5. Gochman, 2. ↩

6. Arnold, "Fred Herzog," 5.↩

7. Bill Jeffries, "Bystanders in Terminal City: The Street Photograph in Vancouver 1955 to 1985," in Unfinished Business: Vancouver Street Photographs 1955 to 1985 (Vancouver: Presentation House Gallery, 2005), 3. ↩

8. Helga Pakasaar, "Fred Herzog," in Fred Herzog: Locations (Vancouver: Equinox Galler, 2009), 6. ↩

9. Stephen Osborne, "Cities Disappear," in Unfinished Business: Vancouver Street Photographs 1955 to 1985 (Vancouver: Presentation House Gallery, 2005), 2.↩

10. Stephen Waddell, "Fred Herzog in Conversation with Stephen Waddell," in Fred Herzog Photographs (Berlin: Hatje Cantz, 181.↩

11. Arnold, "Fred Herzog," 8.↩

12. Grant Arnold, "An Interview With Fred Herzog," in Fred Herzog: Vancouver Photographs (Vancouver: Douglas & McIntyre, 2007), 27. ↩

13. Arnold, "Interview," 29.↩

14. Michael Turner, "Fred and Ethel," in Fred Herzog: Vancouver Photographs (Vancouver: Douglas & McIntyre, 2007), 142-143.↩

15. Turner, 138.↩

16. The Georgia Straight, April 27-May 2, 1979, p.6.↩

17. Jeff Sommers and Nick Blomley, "Every Building on 100 West Hastings," in Stan Douglas, Every Building on 100 West Hastings (Vancouver, Arsenal Pulp Press, 2002), 33.↩

18. Sommers and Blomley, 30.↩

19. Sommers and Blomley, 38.↩

20. See John Armstron, Guilty of Everything (Vancouver: New Star Books, 2001); Joe Keithley, I Shithead: A Life in Punk (Vancouver: Arsenal Pulp Press, 2003).↩

21. See, Katherine Hill, "Our Neon Nightmare: The Role of the Civic Arts Committee in Dismantling Vancouver's Neon Sign Jungle, 1957-1974," in British Columbia History 46 no.3 (2013), 5-14; Glowing in the Dark, Documentary (Moving Images Distribution, 1997).↩

22. Raphael Samuel, Theatres of Memory (London: Verson, 1994), 351.↩

No comments:

Post a Comment